TV broadcast fuels interest in numerous artifacts

Rising numbers of visitors are heading to Sanxingdui Museum in Guanghan, Sichuan province, despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Luo Shan, a young receptionist at the venue, is frequently asked by early-morning arrivals why they cannot find a guard to show them around.

The museum employs some guides, but they have been unable to cope with the sudden influx of visitors, Luo said.

On Saturday, more than 9,000 people visited the museum, over four times the number on a typical weekend. Ticket sales reached 510,000 yuan ($77,830), the second-highest daily total since it opened in 1997.

The surge in visitors was triggered by a live broadcast of relics excavated from six newly discovered sacrificial pits at the Sanxingdui Ruins site. The transmission aired on China Central Television for three days from March 20.

At the site, more than 500 artifacts, including gold masks, bronze items, ivory, jade and textiles, have been unearthed from the pits, which are 3,200 to 4,000 years old.

The broadcast fueled visitors’ interest in numerous artifacts unearthed earlier at the site, which are on display at the museum.

Situated 40 kilometers north of Chengdu, capital of Sichuan, the site covers 12 square kilometers and contains the ruins of an ancient city, sacrificial pits, residential quarters and tombs.

Scholars believe the site was established between 2,800 and 4,800 years ago, and the archaeological discoveries show that it was a highly developed and prosperous cultural hub in ancient times.

Chen Xiaodan, a leading archaeologist in Chengdu who took part in excavations at the site in the 1980s, said it was discovered by accident, adding that it “seemed to appear from nowhere”.

In 1929, Yan Daocheng, a villager in Guanghan, unearthed a pit full of jade and stone artifacts while repairing a sewage ditch at the side of his house.

The artifacts quickly became known among antique dealers as “The Jadeware of Guanghan”. The popularity of the jade, in turn, attracted archaeologists’ attention, Chen said.

In 1933, an archaeological team headed by David Crockett Graham, who came from the United States and was curator of the West China Union University museum in Chengdu, headed to the site to carry out the first formal excavation work.

From the 1930s onward, many archaeologists conducted excavations at the location, but all of them were in vain, as no significant discoveries were made.

The breakthrough came in the 1980s. The remains of large palaces and parts of the eastern, western and southern city walls were found at the site in 1984, followed two years later by the discovery of two large sacrificial pits.

The findings confirmed that the site housed the ruins of an ancient city that was the political, economic and cultural center of the Shu Kingdom. In ancient times, Sichuan was known as Shu.

Convincing proof

The site is viewed as one of the most important archaeological discoveries made in China during the 20th century.

Chen said that before the excavation work was carried out, it was thought that Sichuan had a 3,000-year history. Thanks to this work, it is now believed that civilization came to Sichuan 5,000 years ago.

Duan Yu, a historian with the Sichuan Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, said the Sanxingdui site, located on the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, is also convincing proof that the origins of Chinese civilization are diverse, as it scotches theories that the Yellow River was the sole origin.

The Sanxingdui Museum, located alongside the tranquil Yazi River, draws visitors from different parts of the world, who are greeted by the sight of large bronze masks and bronze human heads.

The most grotesque and awe-inspiring mask, which is 138 centimeters wide and 66 cm high, features protruding eyes.

The eyes are slanted and sufficiently elongated to accommodate two cylindrical eyeballs, which protrude 16 cm in a manner of extreme exaggeration. The two ears are fully outstretched and have tips shaped like pointed fans.

Efforts are being made to confirm that the image is that of the Shu people’s ancestor, Can Cong.

According to written records in Chinese literature, a series of dynastic courts rose and fell during the Shu Kingdom, including those founded by ethnic leaders from the Can Cong, Bo Guan and Kai Ming clans.

The Can Cong clan was the oldest to establish a court in the Shu Kingdom. According to one Chinese annal, “Its king had protruding eyes and he was the first proclaimed king in the kingdom’s history.”

According to researchers, an odd appearance, such as that featured on the mask, would have indicated to the Shu people a person holding an illustrious position.

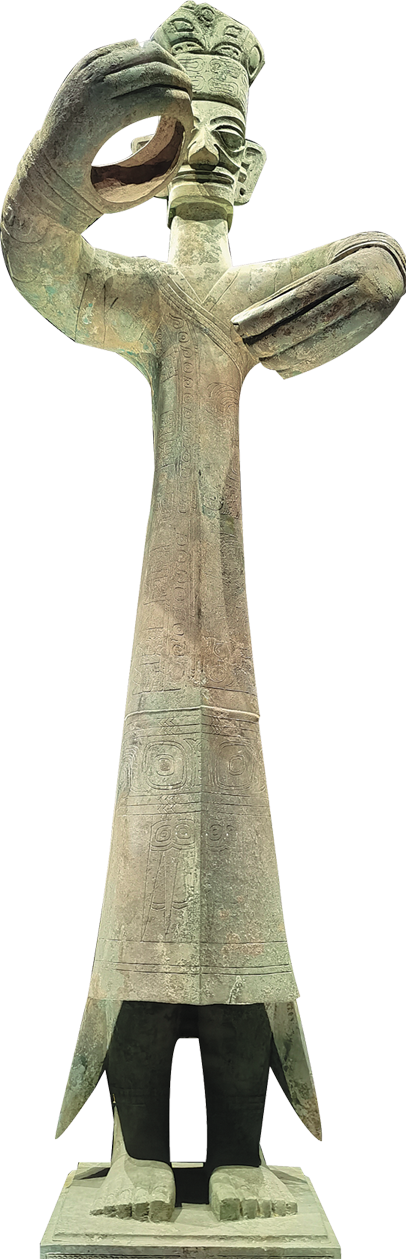

The numerous bronze sculptures at the Sanxingdui Museum include an impressive statue of a barefoot man wearing anklets, his hands clenched. The figure is 180 cm high, while the entire statue, which is thought to represent a king from the Shu Kingdom, is nearly 261 cm tall, including the base.

More than 3,100 years old, the statue is crowned with a sun motif and boasts three layers of tight, short-sleeved bronze “clothing” decorated with a dragon pattern and overlaid with a checked ribbon.

Huang Nengfu, the late professor of arts and design at Tsinghua University in Beijing, who was an eminent researcher of Chinese clothing from different dynasties, considered the garment to be the oldest dragon robe in existence in China. He also thought that the pattern featured renowned Shu embroidery.

According to Wang Yuqing, a Chinese clothing historian based in Taiwan, the garment changed the traditional view that Shu embroidery originated in the mid-Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Instead, it shows that it comes from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC).

A garment company in Beijing has produced a silk robe to match that adorning statue of the barefoot man in anklets.

A ceremony to mark completion of the robe, which is on display at the Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum, was held in the Great Hall of the People in the Chinese capital in 2007.

Gold items on display at the Sanxingdui Museum, including a cane, masks and gold leaf decorations in the shape of a tiger and a fish, are known for their quality and diversity.

Ingenious and exquisite craftsmanship requiring gold-processing techniques such as pounding, molding, welding and chiseling, went into making the items, which showcase the highest level of gold smelting and processing technology in China’s early history.

Wooden core

The artifacts on view at the museum are made from a gold and copper alloy, with gold accounting for 85 percent of their composition.

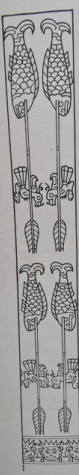

The cane, which is 143 cm long, 2.3 cm in diameter and weighs about 463 grams, consists of a wooden core, around which is wrapped pounded gold leaf. The wood has decayed, leaving only residue, but the gold leaf remains intact.

The design features two profiles, each of a sorcerer’s head with a five-point crown, wearing triangular earrings and sporting broad smiles. There are also identical groups of decorative patterns, each featuring of a pair of birds and fish, back-to-back. An arrow overlaps the birds’ necks and fish heads.

The majority of researchers think a cane was an important item in the ancient Shu king’s regalia, symbolizing his political authority and divine power under the rule of theocracy.

Among ancient cultures in Egypt, Babylon, Greece and western Asia, a cane was commonly regarded as the symbol of the highest state power.

Some scholars speculate that the gold cane from the Sanxingdui site may have originated from northeast or western Asia and resulted from cultural exchanges between two civilizations.

It was unearthed at the site in 1986 after the Sichuan Provincial Archaeological Team took action to stop a local brick factory digging up the area.

Chen, the archaeologist who led the excavation team at the site, said that after the cane was found, he thought that it was made from gold, but he told onlookers it was copper, in case anybody tried to make off with it.

In response to a request from the team, the Guanghan county government sent 36 soldiers to guard the site where the cane was found.

The poor state of the artifacts on display at the Sanxingdui Museum, and their burial conditions, indicate that they had been intentionally burned or destroyed. A large fire appears to have caused the items to become charred, ruptured, disfigured, blistered or even to have completely melted.

According to researchers, it was common practice to set sacrificial offerings ablaze in ancient China.

The site where the two large sacrificial pits were unearthed in 1986 lies just 2.8 kilometers west of the Sanxingdui Museum. Chen said most of the key exhibits at the museum come from the two pits.

Ning Guoxia contributed to the story.

huangzhiling@chinadaily.com.cn

Post time: Apr-07-2021